Should have run upstairs to thump on Georgie’s door, I would have seen the note pinned to the wood alerting the world that she’d been selected for the sleep-study and was in seclusion at a medical compound somewhere in the city. Instead I walked the grassy parkway in the warm night, my tattoo radiating heat like a sunburn. The breeze felt like the dry air that rushes out from a baking oven when you lower the door, it didn’t help at all. Only marginally better than the cramped apartment and my pathetic fan whirring its futile breath around the room. I walked the parkway and it was lively with others escaping their sweltering homes, lots of dogs in the grass and beer on the benches. I turned down the cobblestones to UqBar and shoved the swinging doors open.

The stink of old kegs and a century of spilt liquor smacked me in the nose. I understood that to adjust to the cigarette haze hanging like a cloud cover I would be forced to smoke one myself. At least a cigarette would have a filter, you know? UqBar was packed. Not what I expected, but I guess the heat was making everyone nuts, making everyone crave a beer and respite from the terrible warm of their apartments. And if there’d only been the usual four or five people slumped on the bar, UqBar would have been pretty cool, a darkened cave, the walls black, a trough of ice behind the bar. But all the yahoos and their body heat and sweaty t-shirts had ruined it. They were crazy with the relentless summer and were drunk already and dancing, going mad, their bodies’ humidity rising into a human smog that made the air swampy. I was hoping Georgie showed up soon so we could split, maybe plant our asses on the smooth green grass of the parkway and play with other people’s dogs or something.

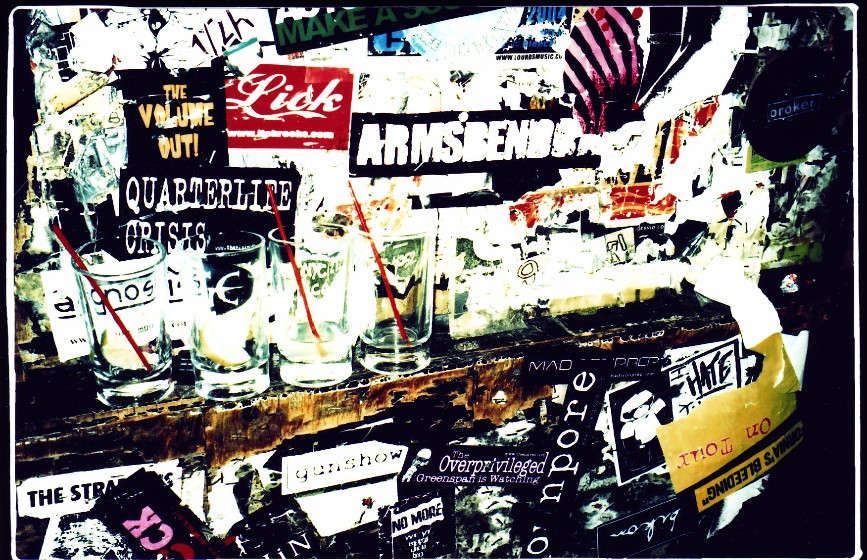

I found a tall stool alongside the wall and got to absentmindedly picking at the band stickers plastered all over the place. The narrow ledge was cluttered with empty cocktail glasses, their little red straws dry and lonely. Willie the bartender looked seriously stressed out, his ruddy Irish face even redder and splotchier with this bad weather and the motion of keeping up with the throngs banging on his counter for their drinks.

Wednesday nights I meet up with Georgie and we drink soda waters Willie throws down for free, fizzing them up as we empty them, plunking a fat wedge of lime into the bubbles. Typically he settles down at the far end of the bar, giving me and Georgie our privacy, and gets to work writing a play based on his dramatic Irish alcoholic family. Wednesday nights are a funny at the UqBar: me and Georgie with our non-drink drinks, a scattering of olde tyme boozers, hard-drinking senior citizens whose cauliflower noses burst with gin blossom bouquets. They resent the bar’s switch from a dank townie sports bar to a hangout for bike messengers and artists with bands on the weekends. They hate change generally and change that affects their drinking in particular, but instead of scuffling over to Dapper’s or Patâ’s for their watery whiskeys they keep an allegiance to a long-past time, their tired asses hugging the busted barstools, getting tanked, glaring at everyone and starting sad little fights on occasion. So there’s us, there’s them, and somewhere in the middle is William, tossing back a shot of something every so-many-pages, never complaining about the utter lack of tips because Wednesday nights leave him alone. No customers to yank him out of the flow of his story, no visits from his dad, both the owner of the establishment and the star of Willie’s play.

I felt bad bothering Willie tonight. He was so hectic, and he hates to work. His orange hair was tugged into a messy ponytail, I was jealous of the teensy breeze it must have created as it swung against his neck. I wanted a water but I didn’t want to hassle him and I didn’t want to get up and lose my seat to a looser. I sniffed at the glasses in the lineup before me. Sniff sniff, the supposed smell-less smell of vodka cut with a juice. Sniff sniff, the sickly sweet stink of gin. The glasses with a bit of syrupy brown pooled at the bottom I ignored, they were obviously whiskey dregs, or rum and cokes. This is my favorite bad game to play with myself. Sniff out an abandoned drink, do my best–my very best–to discern its contents and, sure it’s just a harmless shot of water, toss it back. A sort of Russian roulette, if you will. But I haven’t been wrong yet. As it is an obviously twisted game for a recovering drunk like myself to play, nobody in my life lets me indulge. Like a teenage girl hiding out in her bathroom with a razor, I do my secret sniffing on the rare occasions I’m alone at a bar. Georgie, wise to the fucked-up customs of my head, even goes so far as to arrive at UqBar fifteen minutes before my arrival, so I’m under her watchful stare the whole night. But I wouldn’t do it around anyone, anyway. It’s a private ritual, like nose-picking but really, really bad for you. Bad for me.

Anyway, Willie must have spotted me with my snout in a glass cause he came swaggering over, pushing through the loaf of people globbed throughout the bar, and sloshed me a nice, clean glass of water. Water bubbling pure, honest bubbles. Water hugging a green jewel of lime. Thanks, Willie I said. He clanked the empty glasses together in his huge paws, knocking the straws to the ground. Fuckin’ Crazy In Here, he bitched. Can’t Keep Up With These People. Where The Fuck They Come From? We looked around at the townies, dudes you’d more likely see throwing darts over at Dapper’s, ladies with badly bleached mops of hair and tiny terry cloth outfits; weekend regulars drinking mid-week beers–quiet indie kids sweating in their black jeans, hairspray melting on their black hairdos. And the old guys, the geezers. It’s too hot for them in here, I motioned to death row, the curve of the bar closest to the door, where they clustered like moody crows. One of them’s gonna kick it someday, I told him. Then what’ll you do? I Got Practice With That Sort Of Thing, Willie shook his ponytail. They’ll Be In Good Hands. Willie clapped me on the shoulder and I flinched. Shit, he drew back his fingers gummy with my tattoo medicine. What’s This? He tried to back up for a look and rear-ended a frat-looking kid in a tight white baseball hat. Whiteheads, me and Monica called them. Monica being my incredibly recent ex-girlfriend but you, being my diary, already know that. The whitehead started honking, like Willie was trying to freak him on the dance floor and make him a fag or something. When Willie pulled himself to his full height, hands filled with glass, the Whitehead realized he was the bartender and got friendly again. Sorry, Bro! Can You Pour Me A Guinness?

Yeah, Willie gave a sharp nod, all the niceness sucked dry from his face. He turned back to me. We’ll Talk About That Later, Right? Holler When Georgie Shows Up, I’ll Bring Ya’s More Water. I watched him squeeze between a thick wall of flesh and disappear.

And then there was Monica. I think she’d been in the corner behind death row since I got there, but a guy who’d been hunched over the bar straightened up, and in the gap between his undershirt and the drooled-upon bar below, I saw her there and in that instant she saw me. I felt a rush of hot and cold badness, I think it was anxiety, anxiety and anger, like what the fuck was she doing in my bar, she knows me and Georgie hang out here every Wednesday, were we going to have to do that stupid fucking thing where you negotiate where and when we can and can’t go to the various bars and coffeehouses that make up our lives? I’d thought we could do better then that, thought that common sense and basic kindness would keep her out of my few regular haunts and there she was, her intensely curly hair pulled into a knot on the top of her head, sweat shining the makeup from her face. And I felt a plain swell of sadness and simple fear. The first few days of a breakup are crucial alone days. The risk of getting back together out of basic fear, neediness and habit are strong and it was my plan to avoid Monica until I was stronger then all my most pathetic inclinations.

That’ Water, I Hope? She was there before me, being little and wily and able to slink and shove her way through a crowd with relative grace. And I said, Yeah, Of Course and was annoyed that she’d think I’d be so dramatic as to get drunk over her when I was the one that ended the whole thing. I didn’t need her mothering me or framing me as some fragile alcoholic. I wondered if she’d seen me sniffing the glasses earlier. Her fingernails were painted with elaborate leopard landscapes, pink and red leopard. The tiny rhinestone on her longest pinky-nail flashed and I remembered the balls of soggy cotton she’d leave around my apartment, stinking like poison and nail polish melted into the fiber, and I felt a wash of regret. I’ll never see those cotton balls again. Unless I find one, weeks from now, under the sink in the bathroom, behind the toilet, and am made unbearably sad by it. But this is what I wanted, right? Something to feel, some sort of life, even the life of a miserable and heartsick fuckup.

Why are you here? I asked her. I know I was pouting or talking in a fight-starting voice but I couldn’t help it. It was so loud at UqBar. Willie was blaring some awful CD, real slit-your-wrist tunes, depressing Radiohead or something. The mournful keens filled the bar and still the drunk girls on the stage danced,a s if to some Britney Spears track on endless repeat in their heads. Why was Willie playing such bleak music? It was like we were all in some indie film about grim alcoholic drama and this was the soundtrack.

I Came With Tracy, Monica said, and I looked but the old drunk had resumed his face-first plunge into the bar, blocking my view. Why Are You Here? Well, I’m not drinking, I snapped defensively. I’m waiting for Georgie, like always.

Georgieâ’s Gone, she told me. Georgie’s Doing a Sleep Study, She’ll be Gone All Week. How do you know? I asked. I was sounding more and more like a child, but it was a downhill movement that I couldn’t quite stop. I don’t want to talk to you when you’re drunk, I told Monica, even though I did rather like her when she was drunk. She got extra silly and tended to take her clothes off in public. Well, Talk To Me Now, Then, she said, tinkling her glass. Before I Get Drunk. By the toxic green of her glass and the sweet and sour odor emanating from the rim I guessed it was a Midori melonball. A Midori melonball, I scoffed. This was stupid, this was terrible. This was why we’d broken up–a whole lot of numbness punctuated by useless bickering. Tracy’s Drinking Irish Car Bombs, she snarked, If That’s More Real For You.

Listen, I said, how did you find out Georgie’s gone, and who’s watching the bees? Georgie made part of her money renting out her body to various medical studies, and she made the other part by embarking upon short-lived entrepreneurial experiments. Currently she is keeping a hive of bees in the backyard, in hopes of starting a honey dynasty. I’m Watching Them, Monica said. Why you? I felt totally betrayed. Georgie takes off to some sleep torture and recruits Monica to baby the bees? So that means you’re going to be at the apartment all the time?

Not Yours, she said. We Won’t Have To See Each Other.

You’ll be in the yard, I accused. I’ll totally see you.

Pull The Blinds, she shrugged. Don’t Look Out The Window.

I’ll know you’re there, I said. Don’t act like it’s not a big deal.

Georgie Asked Me. Now she was whining.

I can do it, I said. It’s my fucking yard. Why don’t I just do it.

Because You Hate It, Monica said. You Hate The Bees. You’re Scared Of The Bees.

It is true that the bees stung me repeatedly last time I tried to care for them, when Georgie had gone in for a speed study, totally ruining her so-called sobriety by having medical technicians administer government-issue crystal meth straight into her veins. It is true that I almost killed the bees, much as Georgie almost killed herself, submitting to such a jackass experiment. There Was A Fifty Percent Chance That I’d Just Get The Placebo, she’d rationed. Georgie’s Russian roulette. A whole lot dumber then mine, if you asked me. But Monica, it’s true, Monica loved the bees. She was fucking Snow White with them, they buzzed around her like she was their one true queen, they let her pet the fuzz of their backs with her littlest finger.

I Don’t Know Why Georgie Didn’t Tell You, Monica went on. When Did You Last Talk To Her? And I thought and I thought and I realized that I hadn’t talked to Georgie all week. Even our usual Wednesday the week before had been cut short. Hmph, I snorted.

What’s This? Monica said, her voice a rush of alarm and surprise. I Got A Tattoo, I said proudly. Life goes on, right? Here I am, freshly tattooed, part of the flow of life itself, giving myself a little hurt, just a human, hurting. I smiled.

I Thought You’re Broke, Monica accused. She squinted at it. “Joy and Monstrosity.” She paused. That’s From That Song. You Got A Tattoo Of The Song We Broke Up To. And You Have No Money.

I quit therapy, I explained. It was my therapy money. The tattooist gave me a deal. Timotha? You know her?

Monica was staring. She took a hard suck on her straw and swallowed. Her leopard nails tapped the glasses in swift little taps. You Think That’s Smart? Quitting Therapy? Quitting Therapy? Breaking Up Like This? She swallowed hard again even though her mouth was opened. She swallowed like she was going trying to swallow her very throat turn it inside-out like a crazy magician’s trick. Are You Sabotaging Your Life, Annabella?

I don’t know, I said. I really might be. We stared at each other and I saw a moat of tears flooding up behind her eye makeup and I grabbed her wrist. She clutched her drink harder and shook me off.

Jesus, I don’t want your fucking drink! I yelled. Probably I did want her drink, but that’s not why I grabbed her wrist. I grabbed her wrist to say, you don’t want to cry here, you don’t want to cry in front of me, go back to Tracy. I didn’t grab it because I’m some sort of booze fiend with no self-control. I got a sickening flash of Monica talking to someone–her next girlfriend, maybe a boyfriend, maybe just someone we both knew together, saying, “Oh yeah Annabella is such an alcoholic, it’s really intense, it was so hard to be with her . . . you didn’t know? No, she has no control, it was really, really difficult.” And the new girlfriend or maybe boyfriend would hug her tight and smooth her wild curls and they would all feel safe in their lack of alcoholism, or our mutual friend would cluck and say that’s awful and the pity would slosh back and forth between them.

You Are Such An Asshole, Monica said.

This makes it easier, I said. Just hate me, then. Sure. Then there can be a bad guy, I’ll be the bad guy. And my alcoholism can be the reason and now you’ve got a whole little story to tell everyone about why we broke up. To tell yourself. Good-bye. I slurped my water. The carbonation felt violent, seared my throat, made me choke a little. Made my eyes tear up. I waved my hand. Really, I said. Go back to Tracy. You left her in the corner forever ago. This is stupid. I’m outta here. I felt dumb for having used the phrase “outta hereâ” but really I was shaking.

You Got A Tattoo Of The Last Song We Had Sex To, Monica said.

I know, it looks really bad, I said.

You Mean It Seems Crazy? she asked.

I nodded. Yeah.

Because It Looks Really Beautiful. But It Seems Really Fucked Up.

I left the bar. I slammed and shoved my way past Monica and into the mix of people. The bad sad music howled and the drunks chattered and I chucked the swinging door out into Boston and the hot hot air hit me in the face. I had nowhere to go, so I went home.

Michelle Tea is the author of Valencia, The Chelsea Whistle, Rent Girl, Against Memoir, and many other books. She is the cofounder of the notorious all-girl poetry roadshow Sister Split, and continues to drag herself and other brave performers across the US on grueling performance-art boot camps. Born and raised in Chelsea, Massachusetts, she presently lives in San Francisco with her transboyfriend and their weird cat. Click here to read more of her work and find out about upcoming readings.

Subscribe to get new flash fictions in twice a month in your inbox.

Submit your flash fiction or personal essays to Fiction Attic.