a short story by Mark Pritchard

When the doctors ask me what I remember, I close my eyes and repeat my story: Tired of life in the ruins of Western society, of living in a cramped dormitory with hundreds of other sad, middle-aged men, I signed up for Superdeath. I went expecting that, like nearly everyone else who takes the drug Shiny, I would experience ecstasy, super strength, complete transcendence and freedom from guilt and the past, and death, all within 48 hours.

That is the purpose of attending Superdeath: a final, superhuman blowout of dancing and sex, ending in blissful slumber from which the attendees never wake up. Because Shiny kills 99.999 percent of those who take it.

It wasn’t hard to decide to join them. After the pandemic of the early 21st century, the economic collapse that accompanied it, and the ecological catastrophes that followed that, I had been unemployed for years. Me and hundreds of millions of others. Great legions of us were in prison, legions more were dead. Most of the remainder were, like me, housed in cheap dormitories that had been constructed in dead malls and superstores. There they fed us cheap, disgusting food, permitted us one hour of exercise per week, and prevented us from reading, writing or consuming any media other than a single television channel. Blaring in every room, wall-mounted televisions showed a supposedly calming montage of nature scenes taped during the late 20th century, set to music from the 19th. The montage lasted exactly 18 hours without repeating. When it flicked off, you went to bed. When it flicked on, you got up and ate. That was life.

If that seems bad, consider: someone has to cook that food. Someone has to clean the toilets and do the laundry. These tasks are not done by residents, as we were called. They are done by workers, government workers. These workers have their own restrictions; they are forbidden to interact with the residents. In any case, they don’t–or pretend they don’t–understand English.

Getting one of those jobs was not possible, because the workers were foreign. Going to work for anyone else was not possible, because there were no other jobs. Wandering the streets had become less and less possible, as police tended to pick people up and take them to the dormitories, or to jail. If they didn’t detain you, you were sure to be attacked by roving gangs before you made it out of the city. And if you made it out of the city, there was nowhere to go. It was said there were groups in the mountains, living outside the system and surviving. But I knew this was not true, because in my final job I had worked for a mining concern, and I learned something that was hidden from everyone: Thanks to the mining concern, the mountains no longer existed.

So, despair. And among the many ways of killing yourself–suicide by wall, by self-strangulation, by cop–the alternative of Superdeath is immensely preferable. Not only is it pleasurable, and certain. It’s free. The authorities support it, even though it costs money to stage Superdeath once a week. Because it’s cheaper to kill people by the thousands and incinerate their bodies than it is to feed and house them. There’s nothing sinister about it, it’s not like they turn us into pet food or something. It’s just economics.

After going through the month-long intake process, during which I signed countless forms acknowledging I wanted to kill myself, and being shriven from my few possessions and my legal existence, I received a message giving a time and place: The Astrodome, Thursday, April 5, at 4:00 pm. A bus took me there, from the WalMart I lived in. No one said goodbye.

end of excerpt

Read this story in its entirety, along with other exclusive fiction by emerging and established writers, when you subscribe to Fiction Attic Press.

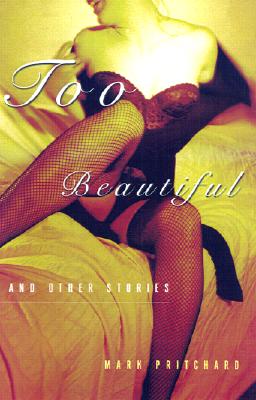

Mark Pritchard is the author of two novels, Make Nice and How They Scored, and two books of short stories, How I Adore You and Too Beautiful and Other Stories, both from San Francisco’s Cleis Press. His story “Instrument” recently appeared in New Lit Salon Press’s “Southern Gothic” anthology, and his story “Woebegone” in Crony. He is the former co-editor and publisher of Frighten the Horses, a sex-and-politics zine that came out from 1990 to 1994, and has lived in San Francisco since 1979.

Mark Pritchard is the author of two novels, Make Nice and How They Scored, and two books of short stories, How I Adore You and Too Beautiful and Other Stories, both from San Francisco’s Cleis Press. His story “Instrument” recently appeared in New Lit Salon Press’s “Southern Gothic” anthology, and his story “Woebegone” in Crony. He is the former co-editor and publisher of Frighten the Horses, a sex-and-politics zine that came out from 1990 to 1994, and has lived in San Francisco since 1979.