I live in a triangle. It’s exactly 213 square miles. It’s a place of Indian curses, ghostly apparitions, cattle mutilations, gigantic snakes, low-flying UFOs, huge birds, and ape-like creatures, seven feet in height, that leave 18-inch footprints. And I live right in the heart of it.

I work here, too, real estate, the only agent in town, although since I haven’t sold anything in six months that will probably change. Soon. The publicity about the reservoir and the Dark Forest Entry Association is killing me. After next month, when 20/20 and 48 Hours come, I doubt anyone will ever take me seriously again.

The activity centers around a 6,000 acre reservoir. Fear of the reservoir goes back 300 years, when the Wampanoag raiding parties hid among the black spruce during the tribe’s war with English settlers.

This much I was willing to discuss with the software engineers who seemed to like everything they saw: a colonial on Hemlock, the Greek Revival on Chestnut Street, the townhouse overlooking the reservoir. I spent little time on features, focusing instead on eliciting cues that might speak to what we call the magic moment, the exact moment the prospective buyer sees themselves in the house being to shown to them. If neither, especially the wife, has a magic moment, no amount of persuasion is going to save the sale. That would seem to explain his sudden departure, but I’m beginning to think it was all the conversation about the reservoir.

“This is it?” the husband asked, on the balcony, sweeping his arm toward the sun-sketched reservoir.

“Pretty, isn’t it? Can you imagine having your morning coffee here, leafing through the paper?”

He said friends were paddling across one day when they came across what looked like a small orange orangutan sitting on an island. “Have you heard that one?”

“No, that’s a new one.”

“You’ve heard the rest, though, right?”

“The rest?” I must have paused a second too long, because the next thing I knew he’d thrust out his hand, a very business-like hand, and was saying thank you for my time. I shook his hand, fumbled for a card from my breast pocket. By then he was at the door, letting himself outside.

I had no more appointments so I went back to the office and copied beauty sheets. Soon my mind went back to everything I’ve tortuously catalogued under “avoid at all cost.” Stories. Stories that could not stand up as theorems, much less even marginally plausible rumors, but they seem to stick in the local collective memory like tar, stories that seem to grow deeper and wider with every rumor and suspicion.

In December 1971, two UFOs were reported to have landed on Route 77. Less than a year later, another was sighted just a few miles up the highway. In 1973, Officer Dan Sweeney claimed he saw a white bird six feet tall and twelve feet from wing to wing soar over Baker Street.

I began to think of myself as I once was. A simple, stable, ordinary high school geometry teacher. Triangles, I always told the students, contain no mysteries. If you know two angles, you can find the third. Pythagoras did all that work centuries ago.

Yet sometimes on the drive home at the end of the day, the darkness closing in on me, I avoid the back roads and yet still find myself reluctantly gazing up at the sky as if it might, out of pity, yield the exculpatory evidence I am sure is there.

Grace Pelletier insisted for years she’d seen Bigfoot coming out of the reservoir. She had a photo. One photo. It certainly looked seven feet tall. But upon closer inspection, by Bert Clemson at the Chamber, it turned out to be a tree stump; its reflection in the water created the illusion it was walking toward a canoe.

But memory is a funny thing. When I am asked, especially by out-of-staters, relos, why property values are so cheap, I avoid reservoir talk. I point out proximity to major highways, vibrant downtown, better-than-average school system.

Inevitably, the conversation circles back to gigantic snakes, low-flying UFOs, huge birds, and ape-like creatures that leave 18-inch footprints coming out of the reservoir, which I tell them I can neither confirm nor deny, which is true, because I’ve seen none of that with my own eyes.

The Dark Forest Entry Association doesn’t help. They’ve festooned Route 77 with “No Trespassing” signs, which is heart-breaking, considering the quaint beauty of the dense woods and moss-tipped stone walls, pictures of which adorn most of the Chamber of Commerce literature I’m fond of mailing, when I have money and time. Yet I often pause and look at the photo of the reservoir that adorns the front of the tri-fold brochure. I swear at times the clouds say “Go Back.”

Driving home this evening, I passed the Dark Entry Road. I felt a tightening in my limbs, a new feeling. So I stopped, put the gear shift in reverse, and backed into the little entrance by the padlocked gate.

Just as I came to a stop, a pick up truck slowed near the entrance. The driver–a large, mustached man in a tan Carthart iron worker’s jacket and John Deere cap–said, after snapping my picture and license tag, “Can I help you?”

“Yes,” I said, “Can we talk?”

“About?”

I told him. I said this foolishness was beginning to get bad for business. He glanced at the magnetic Century 21 signs on my car, and said, “Put the car in drive, step on the gas, and head straight back to where you came from.” I repeated my request. He cocked a double-barrel. Humiliated, I did as told.

When I got home, Milly asked me how my day went. I told her. She said things will get better. How? I want to say.

“Market’s bad for everyone, Dick. It’ll pick up.”

Tonight, as most nights, I’ll wake in the middle of a dream about a serpent with an Indian head dress, something with a long tail that rolls and plunges in the middle of the reservoir. I’ll walk out into my backyard, glance at the house worth exactly half what I paid in 1965, and stare up at the sky for proof, proof what everybody has been saying cannot be true.

Stephen MacKinnon’s work has appeared in Armageddon’s Buffet, Conte, Fugue, Just A Moment, Marginalia, Ontario Review, Plum Biscuit, The Belletrist Review, The Oregon Literary Review, The Southeast Review, The Talking River Review, Triplopia, and Whistling Shade. In addition, his stories have received award recognition from Carve Magazine, Ontario Review, Rosebud and The Southeast Review.

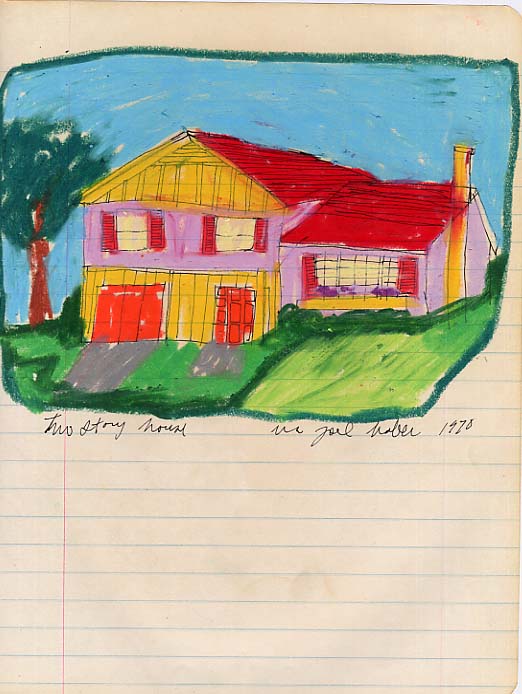

Image by Ira Joel Haber, featured artist. View more of his work here.