The man next door, our neighbor, is behaving badly or so it seems to me. This is not a good thing, I think. How can it be? “It can’t,” my other neighbor says. We decide to have a meeting, invite our other neighbors from farther down the block. Some come, some don’t. Those who don’t show we talk about as well.

We are a community of strangers, made friends by our proximity and the necessity of getting along. Of the neighbor to my left, we wonder, “What’s he up to?” and ask as well, “What about the others? Why aren’t they here?”

Chub Weinman says he saw my neighbor and one of those not with us now talking the other night. He says they looked serious and friendly.

“Ah-ha,” Marty Ferril waves his corn dog.

“Which was it?” I want to know. “Serious or friendly?”

“Both,” Chub Weinman says. “Seriously friendly.”

We nod at this, all of us gathered in Fergie Feckles’ basement show solidarity by tapping our chests and cursing a bit.

We’re worried about the future, we say. Worried about our pensions and our tv shows, things that continue to change beyond our control. Our neighbor in question pretends to be above all this. He drives a blue Saab with tan leather seats, wears stone washed jeans and teaches Humanities at the University. I work for BellSouth, outdoors fixing and setting lines. Chub and Marty and the others, too, work in jobs the same as mine. We know what it means to face adversity, have seen our status and security fucked with, have had to struggle and shift to adjust. To have stuck it out and at the same time, apart from the exceptions caused by human weakness, to remain decent fellows, that is what has made us hard. Our refusal to buckle, this is a page of glory in our history, I tell the others, “This is as we choose to be.”

I’ve tried to explain the situation to Jenny Darne, my buddy Earl Darne’s wife, have told her in no uncertain terms as we undressed in our room at the Tuckit Inn, how conformity is not a dirty word, is the measure of a man’s worth, his willingness to fit in and become part of the whole. “There are certain things a man can’t do,” I flip her over and make sure she gets my point.

Fergie’s wife, Lydia, has made the corn dogs and brought them down to the basement. We have beer and chips. I wonder if its such a good idea to drink during our meeting. Some of my neighbors agree while others don’t. Those of us who do not drink take note of those who do. Those who drink eventually gather together on one side of the room, near the deer head which has come off the wall, too heavy for the mock-wood panels Fergie used to refinish his basement. Andy Futts can’t resist and turns to the deer after a second drink, rolls his hips and says, “Talk about getting head.” Those of us on the other side of the room, not drinking, take note of this as well.

As we are a democracy, I ask the others to vote on what they want to do. I give them a list of four suggestions from which to choose and after some discussion I tell them, “Here’s what I think’s best.”

The neighbor we’ve come to talk about has a son who plays football with our boys on the Renton Eagle’s team. He’s the punter which says it all, I think. My neighbor comes to the games from work, stands by himself, down by the fence, and doesn’t sit up with us in the bleachers. I watch my boy at tackle go and drive the other team’s end into the ground. Jenny Darne never comes to the games. She says football is a brutal sport but she likes it when I slap her rump. I ask her to go away with me for a weekend, say that we can fish and hunt and camp under the stars. The idea makes her laugh. I blush and curse, but as I do she only laughs some more.

All is risk and danger. I feel the threat at work when I hold two ends of a severed line, feel it when I lay in bed and my own wife at a distance snores. I have heard that in his classroom my neighbor lectures on Aglaia, god of charity, Themis, god of justice, and Ares, god of peace. I see him with his own wife walking in the evenings, holding hands in the center of the street. What can such a man be thinking, I wonder? “You see how he’s not like us?” There’s talk he plans to keep his son at home for school and not let him fight in the war. I hear other things about him, strange and unsettling. I’ve shaken his hand before and his skin is soft even as he tries to make his grip hold firm.

“What sort of man is this?” I warn the others. “He isn’t like us.” He’s thin and placid, without spirit and refuses to bay at the moon. “No,” I say and tell them then, “It can’t go on. This sort of bull among us is a danger. We stand and fall on our weakest link and how can we as neighbors rely on such a sorry guy? No, no, no,” I say again and touch my chest, “There’s something we can’t swallow going on over there.”

Steven Gillis’s novel The Weight of Nothing (Brook Street Press, 2005) was a finalist for both the Independent Publishers Book of the Year and ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year.) His first novel, Walter Falls, was published in 2003 and was a finalist for National Book of the Year. He is currently at work on a new novel, Temporary People. A collection of Steve’s stories, Gifaffes, will be published this fall by Atomic Quill Press. Steve teaches writing at Eastern Michigan University and is the founder of 826 Michigan, a nonprofit mentoring and tutoring organization for public school students specializing in reading and writing and a chapter of Dave Eggers’ 826 Valencia. All author proceeds from Steve’s writing go to his 826 Michigan foundation. Steve lives in Ann Arbor with his wife Mary, and children Anna and Zach. Steve is also the co-founder of Dzanc Books.

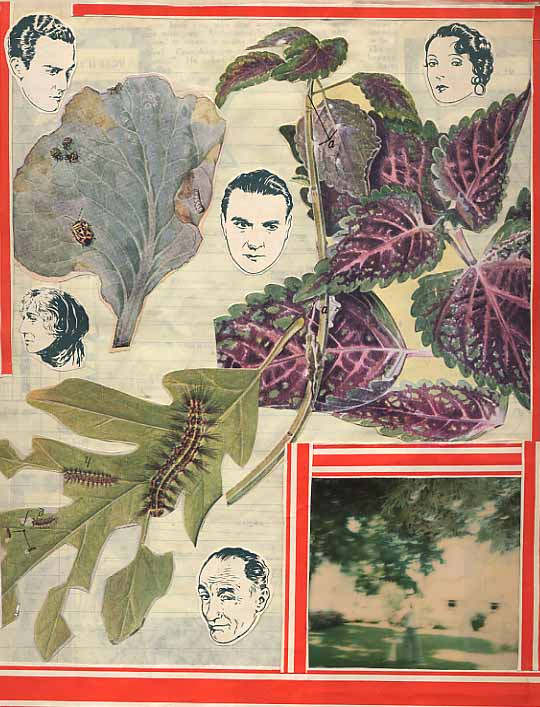

Image by this issue’s feature artist, Ira Joel Haber. You can find more of his work here.